Read "The Marathon Post" as it develops

“I would like to say I remember, but a person only remember(s) if they remember what they remember.” – Allen Toussaint

Bernd Heinrich’s “Why We Run” is written from his own present-tense perspective as he runs a 100 kilometer (62.1 mile) race at the age of forty-one. The majority of the book is presented as a series of flashbacks interspersed throughout the narrative of this seriously long run. I thought that the experience of running my own marathon would help to put the previous six months in perspective for me, and somehow I would finally figure out where I was headed with this project. As I ran the 26.2 miles of mostly familiar territory, I thought that perhaps the connections would start to form and I would cross the finish line four-and-a-half hours later with the Great American Novel perched atop my head like a delicately balanced bowl of water. This of course didn’t happen. In the intervening weeks and months I have gained some insights, but in some ways my obsessive mapping has only gotten me more lost. I have spent most of the last few months without running, writing, or even thinking much about this project, and this I think is where the real perspective has come from.

Near the beginning of this project I went to Alaska on a medical escort that flew directly over New Orleans about twenty-four hours after the arrival of Hurricane Katrina. The pilot dipped the left wing of the plane as we passed to the north of the ruined city, and we all craned our necks to see the shredded roof of the Superdome and the streets glistening in the sunlight as water began to pour in from the breeched levees around the town. At the time we had no idea of the horrors that New Orleans would experience in the weeks, months, and years to come. My post from that day makes mention of the Good Friday earthquake that struck Anchorage in 1964, but it says nothing of the human catastrophe that was unfolding directly below us.

Six months later, and two days after New Orleans’ first post-Katrina Mardi Gras, I’m doing a medical escort flight from Beaumont, Texas to New Orleans for a nursing home patient who was evacuated after the storm. It’s only been four days since the marathon, and two full days of flying on a thirty-seat turbo prop has done nothing for the condition of my legs. I shift restlessly in my seat, convinced that at any second I will dislodge a blood clot from the distended veins in my ankles and I’ll keel over dead from the ensuing pulmonary embolism. My patient is not concerned at all. Her advanced Alzheimer’s disease has erased most of her memories of home, and the recent tragedy of Katrina hasn’t even registered with her. As our plane comes in over the blue-tarp roofs of suburban Jefferson Parish, I think about the memories that we each hold of the ruined city rising up below us. The New Orleans that exists in my patient’s mind began to disintegrate years before the levees finally let go. Undoubtedly, the nursing home to which she is going will look a lot like the one in Beaumont; a facility which could not have been much different from the one she first left in New Orleans. Her connection to the present is tenuous at best, and the city of her past was swallowed long ago by dementia’s rising tide. Her only connection to reality is a persistent and misguided belief that she is waiting to be picked up by her daughters. The nursing staff in Beaumont confirmed that she had three daughters in New Orleans, but none of the staff had had any contact with them in the six months that their mother had been in Beaumont.

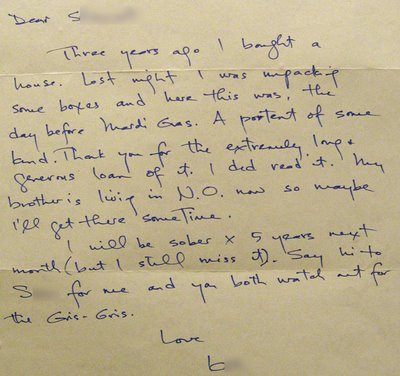

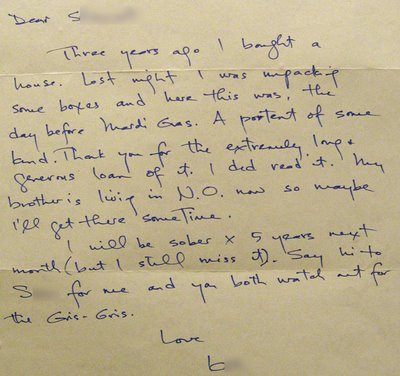

Back at home, I’m thinking about the countless personal histories of New Orleans that now seem so irrelevant. I remember the book “Beautiful Crescent: A History of New Orleans”, one of the first unabashedly subjective histories I had ever encountered, loaned to me by a friend ten years ago and never returned. He had just gotten the book back from an extended loan to another friend and he gave it to me with the promise that I would return it promptly. Today I find the book in a stack of boxes at the back of the house and I read the forward that had impressed me so much ten years ago. “We maintain that there is no definitive history, only stories told with more or less documentation.” As I thumb through the old paperback’s yellowed pages, I find a hand-written letter tucked in at the back cover dated February 19, 1996.

There’s something so sad in that letter. There is an undertone of resignation that I just can’t put my finger on. Here I am ten years later, reading a letter that I could have written myself. A portent of some kind. I haven’t seen S. in at least five years and although I can make no claims as to my continued sobriety, it was in many ways his steadfast refusal to see things from any sort of sober perspective that led us apart. Maybe I’ll get there sometime…

I’m out for one of my first runs since the marathon, and what used to be a simple four mile route is about to kill me. How can this possibly be so hard? I have repeated before that I am not a natural runner, but I think through my six months of training there was a secret part of me that began to feel I had become one, and I was right, but this recent hiatus has permanently altered my development as a runner in the same way that my six months of training forever changed my life as a non-runner. I’ll recover, and I’ll get back to where I was at least, but I am changed.

I am only what I do, and the history of what I have done doesn’t enter into it any more than does my desire for things I would like to do or my lies about things I claim to have done. I am right now, and right now I feel like I’m going to shit my pants. I’d better walk for a few minutes.

It’s here, walking gingerly along the river in the long shadows of the late evening sun that I start to make some connections. The physical manifestations of river and city serve only as backdrops to the many dramas that have played across their stages. As the evacuation of New Orleans finally began, each commandeered school bus took with it pieces of the city that would not return without being changed, if they were to return at all. For months the vibrant, eclectic, and quintessentially American culture of New Orleans came to a halt while its participants scattered across the country to experience new environments and rituals, and to alter those destinations with their presence in much the same way that the Mariel boatlift had changed the face of South Florida twenty-five years ago. The months-long abandonment of New Orleans would have been enough to alter its unique character forever, but the storm’s destruction had erased many of the physical reminders needed to jog the memories of its former occupants on their return.

The experience of New Orleans or Tampa or any other city is immersive, temporal, and elusive: a leaf in the stream of the city’s people, history, geography, and culture. The city’s personality, like that of a man, is a product of these competing and ever-changing forces that can never again be duplicated. Just as a man’s DNA can theoretically be extracted to produce “exact replicas” of himself, the infinitely complex set of influences that created his personality can never be reproduced. In New Orleans this scenario was multiplied by the hundreds of thousands. Katrina dragged her hand slowly through the ant trail of New Orleans, and its occupants had lost the scent and scattered.

The plane to New Orleans had been crowded with hard-hat-toting construction workers, project managers, and government-official-types, each with their own concept of what New Orleans was and, more importantly, what it would become. Most of their ideas had originated in far-flung government offices and had little or no relation to the city of New Orleans, its people, and their unique set of circumstances.

All of my life’s most memorable experiences have started well before dawn. From childhood fishing trips with my father to college road trips, touring with the band, backpacking, and mountain climbing; it seems like anything worth doing requires the use of multiple alarm clocks and a coffee maker that is pre-loaded and ready to go. The morning of February 26th, 2006 is no different. Like some sort of numerologist’s dream, I have chosen to run 26.2 miles on 02-26-2006.

At three o’clock I awake and start my now-familiar long run ritual. Drink thirty-two ounces of water standing naked in the dark at the kitchen sink. Turn on the kettle and see the room lit only by the blue flame of the gas burner. Shower by candlelight. The thought of the kettle boiling away on the stove helps to keep me from luxuriating in the shower’s warmth for too long. Still wrapped in my towel, I pour the steaming water into the French press and stir with a wooden spoon stained a dark brown to the middle of its handle from years of this routine. I turn up the dimmer in the kitchen, letting my eyes adjust gradually to the light. As the coffee steeps, I dress myself slowly. First comes the BodyGlide; a generous coat applied to any surface that might even think about blistering or chafing, then I powder my feet and slather my upper body in sunscreen. My clothes are laid out on the dresser like a seven-year-old on his first day of school, and I slip into them quietly while Jan sleeps. I take my shoes and socks out to the couch and sit down, deliberately lining up each seam over my toes, making sure that everything lies flat and straight. There is something about the act of putting on my shoes that always gets me lost in thought. Somehow, this final act in my morning ritual sets me to thinking about what lies ahead and I sit, one shoe on and the other in hand, “locked in a stare” as Jan would say. I’ve done this all my life, and I’m not the only one in the family. A week ago I watched my brother do the same thing as he got ready for an early flight back to California. Coming to, I think of the nursery rhyme that my stepmother would tease me with as a child, “Diddle, diddle, dumpling, my son John/ Went to bed with his stockings on/ One shoe off, and one shoe on/ Diddle, diddle, dumpling, my son John.”

A large portion of marathon training, I have come to believe, is not directly related to the physical act of running. There are certain adjustments that one’s body must make in terms of metabolism, pacing, stamina, and overall tolerance for abuse, but the vast majority of what is accomplished in the months of training is a little harder to quantify. It is only through constant repetition that the runner begins to gain control over the more subtle and less conscious elements of their performance. The “involuntary” smooth muscles of the digestive tract begin to obey signals from the rest of the body, and on mornings before a long run there is a cleansing that takes place as the body tries to free itself of all unnecessary baggage before embarking on the journey ahead. I have experienced this effect several times now and it has become part of my pre-run ritual, but the last few days have been slightly different. Something inside of me knows that today’s race carries with it the weight of all my previous efforts, and this has manifested itself as a week-long obsession. I have an insatiable desire to do the three things that, according to Lenny Bruce, led to the first laws of civilization: Eat, Sleep, and Crap. I’m locked in the grip of a full-body peristalsis, and I can’t seem to get enough.

Bernd Heinrich’s “Why We Run” is written from his own present-tense perspective as he runs a 100 kilometer (62.1 mile) race at the age of forty-one. The majority of the book is presented as a series of flashbacks interspersed throughout the narrative of this seriously long run. I thought that the experience of running my own marathon would help to put the previous six months in perspective for me, and somehow I would finally figure out where I was headed with this project. As I ran the 26.2 miles of mostly familiar territory, I thought that perhaps the connections would start to form and I would cross the finish line four-and-a-half hours later with the Great American Novel perched atop my head like a delicately balanced bowl of water. This of course didn’t happen. In the intervening weeks and months I have gained some insights, but in some ways my obsessive mapping has only gotten me more lost. I have spent most of the last few months without running, writing, or even thinking much about this project, and this I think is where the real perspective has come from.

Near the beginning of this project I went to Alaska on a medical escort that flew directly over New Orleans about twenty-four hours after the arrival of Hurricane Katrina. The pilot dipped the left wing of the plane as we passed to the north of the ruined city, and we all craned our necks to see the shredded roof of the Superdome and the streets glistening in the sunlight as water began to pour in from the breeched levees around the town. At the time we had no idea of the horrors that New Orleans would experience in the weeks, months, and years to come. My post from that day makes mention of the Good Friday earthquake that struck Anchorage in 1964, but it says nothing of the human catastrophe that was unfolding directly below us.

Six months later, and two days after New Orleans’ first post-Katrina Mardi Gras, I’m doing a medical escort flight from Beaumont, Texas to New Orleans for a nursing home patient who was evacuated after the storm. It’s only been four days since the marathon, and two full days of flying on a thirty-seat turbo prop has done nothing for the condition of my legs. I shift restlessly in my seat, convinced that at any second I will dislodge a blood clot from the distended veins in my ankles and I’ll keel over dead from the ensuing pulmonary embolism. My patient is not concerned at all. Her advanced Alzheimer’s disease has erased most of her memories of home, and the recent tragedy of Katrina hasn’t even registered with her. As our plane comes in over the blue-tarp roofs of suburban Jefferson Parish, I think about the memories that we each hold of the ruined city rising up below us. The New Orleans that exists in my patient’s mind began to disintegrate years before the levees finally let go. Undoubtedly, the nursing home to which she is going will look a lot like the one in Beaumont; a facility which could not have been much different from the one she first left in New Orleans. Her connection to the present is tenuous at best, and the city of her past was swallowed long ago by dementia’s rising tide. Her only connection to reality is a persistent and misguided belief that she is waiting to be picked up by her daughters. The nursing staff in Beaumont confirmed that she had three daughters in New Orleans, but none of the staff had had any contact with them in the six months that their mother had been in Beaumont.

Back at home, I’m thinking about the countless personal histories of New Orleans that now seem so irrelevant. I remember the book “Beautiful Crescent: A History of New Orleans”, one of the first unabashedly subjective histories I had ever encountered, loaned to me by a friend ten years ago and never returned. He had just gotten the book back from an extended loan to another friend and he gave it to me with the promise that I would return it promptly. Today I find the book in a stack of boxes at the back of the house and I read the forward that had impressed me so much ten years ago. “We maintain that there is no definitive history, only stories told with more or less documentation.” As I thumb through the old paperback’s yellowed pages, I find a hand-written letter tucked in at the back cover dated February 19, 1996.

There’s something so sad in that letter. There is an undertone of resignation that I just can’t put my finger on. Here I am ten years later, reading a letter that I could have written myself. A portent of some kind. I haven’t seen S. in at least five years and although I can make no claims as to my continued sobriety, it was in many ways his steadfast refusal to see things from any sort of sober perspective that led us apart. Maybe I’ll get there sometime…

I’m out for one of my first runs since the marathon, and what used to be a simple four mile route is about to kill me. How can this possibly be so hard? I have repeated before that I am not a natural runner, but I think through my six months of training there was a secret part of me that began to feel I had become one, and I was right, but this recent hiatus has permanently altered my development as a runner in the same way that my six months of training forever changed my life as a non-runner. I’ll recover, and I’ll get back to where I was at least, but I am changed.

I am only what I do, and the history of what I have done doesn’t enter into it any more than does my desire for things I would like to do or my lies about things I claim to have done. I am right now, and right now I feel like I’m going to shit my pants. I’d better walk for a few minutes.

It’s here, walking gingerly along the river in the long shadows of the late evening sun that I start to make some connections. The physical manifestations of river and city serve only as backdrops to the many dramas that have played across their stages. As the evacuation of New Orleans finally began, each commandeered school bus took with it pieces of the city that would not return without being changed, if they were to return at all. For months the vibrant, eclectic, and quintessentially American culture of New Orleans came to a halt while its participants scattered across the country to experience new environments and rituals, and to alter those destinations with their presence in much the same way that the Mariel boatlift had changed the face of South Florida twenty-five years ago. The months-long abandonment of New Orleans would have been enough to alter its unique character forever, but the storm’s destruction had erased many of the physical reminders needed to jog the memories of its former occupants on their return.

The experience of New Orleans or Tampa or any other city is immersive, temporal, and elusive: a leaf in the stream of the city’s people, history, geography, and culture. The city’s personality, like that of a man, is a product of these competing and ever-changing forces that can never again be duplicated. Just as a man’s DNA can theoretically be extracted to produce “exact replicas” of himself, the infinitely complex set of influences that created his personality can never be reproduced. In New Orleans this scenario was multiplied by the hundreds of thousands. Katrina dragged her hand slowly through the ant trail of New Orleans, and its occupants had lost the scent and scattered.

The plane to New Orleans had been crowded with hard-hat-toting construction workers, project managers, and government-official-types, each with their own concept of what New Orleans was and, more importantly, what it would become. Most of their ideas had originated in far-flung government offices and had little or no relation to the city of New Orleans, its people, and their unique set of circumstances.

All of my life’s most memorable experiences have started well before dawn. From childhood fishing trips with my father to college road trips, touring with the band, backpacking, and mountain climbing; it seems like anything worth doing requires the use of multiple alarm clocks and a coffee maker that is pre-loaded and ready to go. The morning of February 26th, 2006 is no different. Like some sort of numerologist’s dream, I have chosen to run 26.2 miles on 02-26-2006.

At three o’clock I awake and start my now-familiar long run ritual. Drink thirty-two ounces of water standing naked in the dark at the kitchen sink. Turn on the kettle and see the room lit only by the blue flame of the gas burner. Shower by candlelight. The thought of the kettle boiling away on the stove helps to keep me from luxuriating in the shower’s warmth for too long. Still wrapped in my towel, I pour the steaming water into the French press and stir with a wooden spoon stained a dark brown to the middle of its handle from years of this routine. I turn up the dimmer in the kitchen, letting my eyes adjust gradually to the light. As the coffee steeps, I dress myself slowly. First comes the BodyGlide; a generous coat applied to any surface that might even think about blistering or chafing, then I powder my feet and slather my upper body in sunscreen. My clothes are laid out on the dresser like a seven-year-old on his first day of school, and I slip into them quietly while Jan sleeps. I take my shoes and socks out to the couch and sit down, deliberately lining up each seam over my toes, making sure that everything lies flat and straight. There is something about the act of putting on my shoes that always gets me lost in thought. Somehow, this final act in my morning ritual sets me to thinking about what lies ahead and I sit, one shoe on and the other in hand, “locked in a stare” as Jan would say. I’ve done this all my life, and I’m not the only one in the family. A week ago I watched my brother do the same thing as he got ready for an early flight back to California. Coming to, I think of the nursery rhyme that my stepmother would tease me with as a child, “Diddle, diddle, dumpling, my son John/ Went to bed with his stockings on/ One shoe off, and one shoe on/ Diddle, diddle, dumpling, my son John.”

A large portion of marathon training, I have come to believe, is not directly related to the physical act of running. There are certain adjustments that one’s body must make in terms of metabolism, pacing, stamina, and overall tolerance for abuse, but the vast majority of what is accomplished in the months of training is a little harder to quantify. It is only through constant repetition that the runner begins to gain control over the more subtle and less conscious elements of their performance. The “involuntary” smooth muscles of the digestive tract begin to obey signals from the rest of the body, and on mornings before a long run there is a cleansing that takes place as the body tries to free itself of all unnecessary baggage before embarking on the journey ahead. I have experienced this effect several times now and it has become part of my pre-run ritual, but the last few days have been slightly different. Something inside of me knows that today’s race carries with it the weight of all my previous efforts, and this has manifested itself as a week-long obsession. I have an insatiable desire to do the three things that, according to Lenny Bruce, led to the first laws of civilization: Eat, Sleep, and Crap. I’m locked in the grip of a full-body peristalsis, and I can’t seem to get enough.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home